I managed to separate church and state better than the Supreme Court, until I couldn’t.

By: Emily Hemphill

I was struggling to sit comfortably in a metal folding chair in the living room where I had been spending every Thursday night for the past two years helping out as a group leader for a Rite of Christian Initiation class, a course for those seeking to join the Catholic Church. On this particular night, the assembly was split into small groups, and we were each assigned to determine and defend the Catholic stance on a particular moral issue. My group was assigned the topic of homosexuality … this was going to be fun.

I’d always felt somewhat at odds with certain church teachings. I was the type to engage in theological debates with teachers at my Catholic high school and didn't consider myself overly religious. My doubts became even more pronounced when, last summer, the Supreme Court overturned the rights guaranteed to women over their bodies. What was once an uncomfortable disagreement with the church morphed into what felt like a personal attack. When I finally brought some of my doubts to the priest, I was met with “your beliefs should be aligning with the Church’s.” I was frustrated and hurt, but my fear of confrontation and embedded respect for authority kept my lips sealed.

I felt those feelings rise to the surface that night as I retreated to the corner of the room trying to block out the “one man and one woman” comments; biting on the inside of my cheek hard enough to draw blood. But the guilt began to build in the pit of my stomach. I felt like a passive bystander. How could I silently sit here and not defend the people in my life who were being called sinners? In that moment, I knew I couldn’t be there anymore. Soon after, I stepped down from my role as a group leader and away from the church. But in the weeks following my departure, I started to wish for a new way to worship.

I find it impossible to believe that I am the only liberal Christian in America right now, struggling to balance religious and socio-political beliefs without completely abandoning the Church altogether. I wondered if I could try to find a place where I could embrace my progressive values while still practicing my faith. Was such a balance plausible? And then I spotted a potential answer. A “DISMANTLE RACISM” poster flashed before me, but it was the adjacent sign that really caught my eye: “Trinity Episcopal Church.”

www.trinity-fredericksburg.org

It was a building right next to campus, just a short walk from my old church. For some reason, I’d never paid much attention to it before. This time, the sign struck a chord. A church? Displaying that sign in its front yard? And is that … a rainbow flag next to it? The contradictions were almost too much for my little Catholic brain to compute. I decided almost immediately. I would start attending and see if I could finally answer the question in my mind: Can I be a Christian in 2022?

First Trinity visit:

I started off with the 10 a.m. service. Arriving in my usual fashion – right on time, if not a few seconds late – I sat down and studied my surroundings. I couldn’t recall the last time I had been in another Christian church, but I don’t think I would have noticed a difference if it weren’t for the female priest up on the altar. Definitely not Catholic. Spread out among the pews were mostly elderly churchgoers, though a few younger couples were struggling to keep little kids quiet and still.

As the service progressed, I was taken aback that they followed almost the identical structure and script as the masses I’d attended my entire life. The parallels were comforting. I did catch myself grinning occasionally as the female priest, Mother Cynthia, led the congregation in prayer or delivered the Homily, or sermon. I didn’t know the terminology used in a non-Catholic setting. Growing up only seeing men in priestly robes, I was soon fangirling over Mother Cynthia. As I listened to her preach about hospitality and serving the poor, my mind began to drift. I’d grown up hearing this spiel and I didn’t think the Episcopalians had anything radically different to say on the topic.

An Episcopal church at the New York LGBT Pride March in 2017. | www.dioceseny.org

Described as “Protestant, yet Catholic” – practically oxymoronic in my opinion – the Episcopal Church was originally affiliated with the Church of England, but the two went their separate ways foll]owing the American Revolution. While retaining many characteristics of Catholicism, as I noticed, Episcopalians set themselves apart in several significant ways. In the late 1950s, they began to support civil rights legislation. The first women were ordained as priests in 1974. The Episcopal Church was apparently much more in tune with the times because it was only a couple years later it announced at the General Convention that gay people deserved “acceptance and care from the church” and equal protection under the law. They even ordained a transgender priest in 2005, which would be inconceivable by Catholic standards.

“Equal opportunities in jobs and education is critical not dependent on sex, race, or gender orientation,” said Mother Cynthia. The words of Mother Cynthia snapped me back into the sermon. Now that was a sentence one doesn’t hear often in the Catholic Church. It felt like a safe haven. A place where I could try and integrate my beliefs, both religious and political.

As I left the church that day, I was approached by a few women who seemed quite enthusiastic at seeing a fresh face. Once I had been greeted and promised to return, I made it out of the church where the two priests were shaking hands with everyone and having small conversations. The younger priest – a man probably in his mid 30s who introduced himself as Ethan at the beginning of the service – made his way over to me. I told him a little bit about myself, that I was a college student studying political science and journalism and had no idea what I was going to do with my life. He was friendly and easygoing, very different from the formality I was used to in Catholic priests.

“I’ll shoot you an email sometime this week so we can meet up for coffee or something,” Ethan suggested at some point.

“Great! Thank you,” I said.

“Slay.”

SLAY

???

SLAY ???

Trinity: take two:

On my second visit, Ethan was not at the service, but Mother Cynthia was presiding over the congregation again. She had a way of managing to make eye contact with everyone in the room all at once and welcoming them in with just a spread of her arms. She spent most of her sermon explaining the importance of the Eucharist, as this was the first service where they had wine back since the start of the pandemic. I unconsciously released a small sigh of relief when she said that all were invited to partake in communion with a little twinkle in her eye. Again, I felt comforted that this church experience wasn’t too radically different from what I’d seen before.

This church seemed to be everything I was looking for. Female and slang-wielding priests, accepting of LGBTQ+ people, no requirements, or pressures to conform and I even came across a Committee for Racial Healing on their website; it seemed almost too good to be true. Only a couple hundred yards from the front door of my apartment building, it seemed to hold all of the answers. And yet, I couldn’t figure out why I wasn’t quite overjoyed that I’d found a place I felt like I could fit in. This time, that unease I felt expressed itself through increased skepticism. If Trinity was truly as accepting and progressive as it promoted itself to be, then why were the pews half-empty on Sunday mornings?

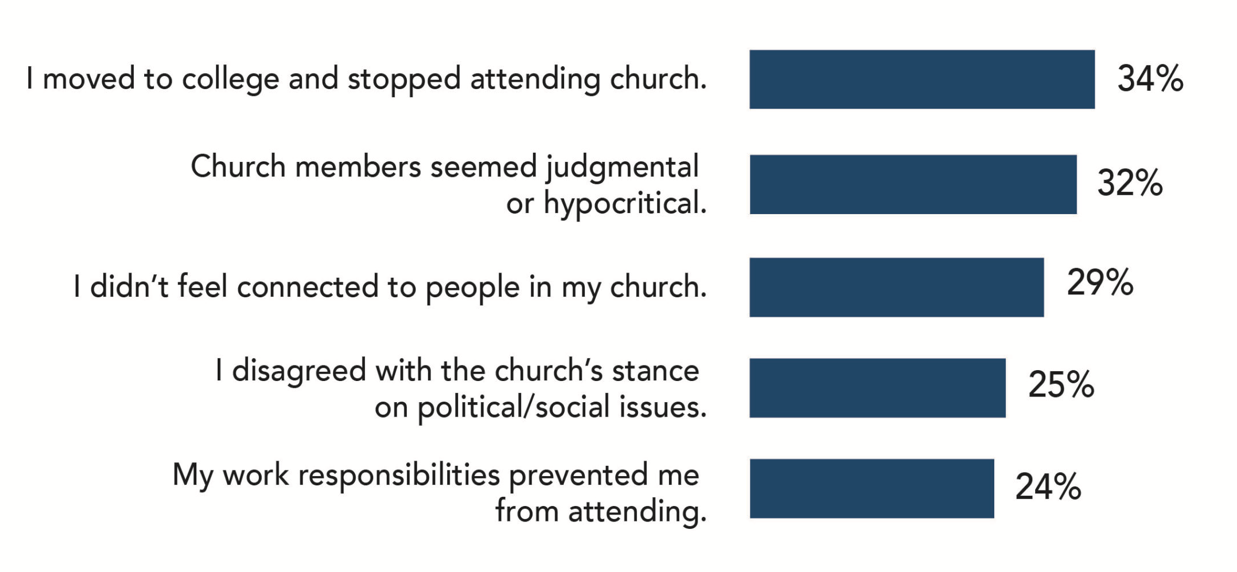

Right as I was thinking this, a girl who I recognized from a class my freshman year sat in front of me. This raised the population of early 20-year-olds in the church to two. Was religion slowly becoming an activity reserved only for boomers and young families aspiring to raise their kids in the church but who soon become the Christmas and Easter church goers as soccer practices, doctors’ appointments and piano lessons consume their every waking moment? That seemed to be what the research suggested. LifeWay Research released a study in 2017 stating that over 65 percent of Americans from the ages of 23-30 stopped regularly attending church services since they turned 18 years old. The group previously conducted a similar survey in 2007 where they found that 52% of “young Christians” cited political concerns as the reason for their exodus from the church.

Top 5 reasons for church dropouts

Young adults (ages 23-30) attending a Protestant church regularly for at least a year in high school

While it was refreshing to be in a place where my secular and spiritual beliefs aligned, I still didn’t feel like I could see myself fitting in there, age-wise. Another thing I’d read in some of the research was that many people my age were trying to practice their faith in other ways. I started to wonder whether I truly did need a church. A cradle Catholic, I’d joined the ranks of plaid-skirt wearing Catholic school girls in third grade and continued cycling through the same two skirts until graduation. When I came to college, I got involved in the Catholic Campus Ministries right away, continued going to Mass on Sundays and began volunteering at the RCIA classes. It felt like a way to stay connected to my faith and family. But now I wondered if all of that was necessary.

It made little sense to me to trust an institution with archaic systems of power still in place and traditions created in a time of patriarchy – whether Catholic or other – to dictate my behaviors and values. I wondered if my faith was something I could still hold onto in a personal, distinct way. Perhaps I didn’t need the physical church or institution anymore. I was just so used to having a building to go to worship and feel connected to my faith. My obvious next question was: would I be able to let go?

Coffee with Ethan:

I walked up the steps of “The House,” glancing over at the progress pride flag hanging in the front window. I stepped through the open doorway and entered into a small living room area, the walls covered in homemade artwork, birthday streamers, Christmas lights and Black Lives Matter posters with two couches lining two corners of the room and folding chairs completing the circle. I knocked on the doorframe and Ethan emerged from an office in the back of the small building.

The Reverend Ethan Lowery | www.trinity-fredericksburg.org

After a quick tour through the rest of the house, we settled back in chairs in the front room. I felt the need to come clean – he is a priest after all – and laid out my recent disagreement with the Catholic faith, my ongoing spiritual investigation and deviation in beliefs. Over the next hour, we discussed our respective religious backgrounds. He was raised in the Episcopal Church in Johnson City, Tenn. Sympathizing with and expressing his regret over my current spiritual turmoil, Ethan talked about wanting to meet each person who stepped foot in The House where they were in their lives, not holding them to any standards or demanding anything of them, “just caring for them as Jesus would.”

He related to the chronic exhaustion that was seemingly permeating everyone’s lives at the moment, recognizing that sometimes all college students need is a place to come and set down their backpacks bursting with essays, assignments, anxiety, insecurities and expectations and just breathe. A community of around eight regulars at the moment – UMW and Germanna students – they hold weekly pizza dinners on Tuesday nights at “The House,” which is what they’ve nicknamed the Episcopal-Lutheran campus ministry building. Another activity mentioned in the newsletter is “Praying Hooky” where the group heads to a local coffee shop on a couple Sunday mornings throughout the semester “for some worldly self-care.”

As intriguing as skipping out on church services with a priest sounded, I couldn’t see myself discussing Bible verses or how to follow my moral compass in a secular college setting over a white chocolate mocha. I was tired of being told of what to believe, how to think and act. I didn’t want one more bad church experience to completely turn me away from any shred of faith left.

“I know how corny this sounds, but I’m just going to go ahead and say it … if you need a priest, you’ve got one here.”

The House | Ethan Lowery

Resolution, but not really:

Thinking more about why I didn’t join the church that seemed like the panacea I was seeking, I started to realize that maybe it was too soon for me. Not much time had passed since I’d left the Catholic Campus Ministry, and I was still trying to process through what had happened, my religious past and what that future might look like now. I knew deep down that I had done what was right for me, especially if I wanted to maintain some spiritual life down the road, but I think I’d been in the church too long to not feel a little of that classic Catholic guilt. I wasn’t ready to put my faith in a new church and open myself back up when I still felt so conflicted about what I’d just experienced. I needed some resolution, which I knew would take some time.

As I spoke with classmates and friends, their stories regarding church had all the same themes: differences in beliefs, pressures to conform and the feelings of not fitting in, not being as good or devout, or not doing enough to meet impossibly high expectations. Still, many of them still longed for a feeling of belonging, of putting their trust in something greater than them I have been told that one does not get to pick and choose what they believe from the Catholic faith, but that’s what I feel I need to do in order to stay connected with some form of church. I will hold onto the good I have seen and understand that there will be certain aspects that I will not be able to reconcile with in my heart.

Once I sort that out, then maybe I’ll be ready to start attending another church again. Or maybe I won’t need to.